When Christopher Luxon was selling soap powder for Unilever in Canada, that country’s indigenous people were calling for decolonisation – loudly. Canada’s First Nations people, in contact with, and often inspired by the efforts of tangata whenua from Aotearoa, were determined to make white Canadians face up to their past. Their agitation should have engaged Luxon’s attention.

It should have made him think. Not only about the issues being brought forward by indigenous Canadians. Because their issues, had he thought about it, were Māori issues, too. What was happening in Canada was also happening in New Zealand.

When Luxon came home to take up the leadership of Air New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern made him one of her government’s business advisers. Woke ideology was shaking up every aspect of New Zealand. The land, the sea and, yes, even Air New Zealand safety ads.

The names of New Zealand’s cities were changing. So, too, were the names of government departments. Even the weather reports were being indigenised. And, in the midst of all this indigenisation and decolonisation, Luxon was contemplating a run at political power.

How could he not have noticed what was going on all around him? The Māori caucus’ push for tino rangatiratanga? The emergence of the concept of co-governance? The content of the He Puapua Report? The late Moana Jackson’s behind-the-scenes constitutional activism? Did it not occur to him that something powerful, something fundamental to New Zealand’s future was afoot?

Across the entire New Zealand right there was a growing sense of unease. How did the man miss it? Or, allowing that he did notice it, how could he dismiss it as an issue of secondary importance?

Had Luxon even noticed the scorn and derision that greeted Ardern’s inability to accurately or coherently interpret the three articles of the Treaty of Waitangi? Did he “get it”? That knowledge of the Treaty, or, and this should have been a clue, Te Tiriti, is an essential component of a New Zealand prime minister’s skill-set?

Truth –to tell, it has been ever since the late 1980s when Claudia Orange’s The Treaty of Waitangi was published. Back then, intelligent business leaders like Hugh Fletcher distributed copies of the book to all his senior executives with strict instructions that it be read and absorbed.

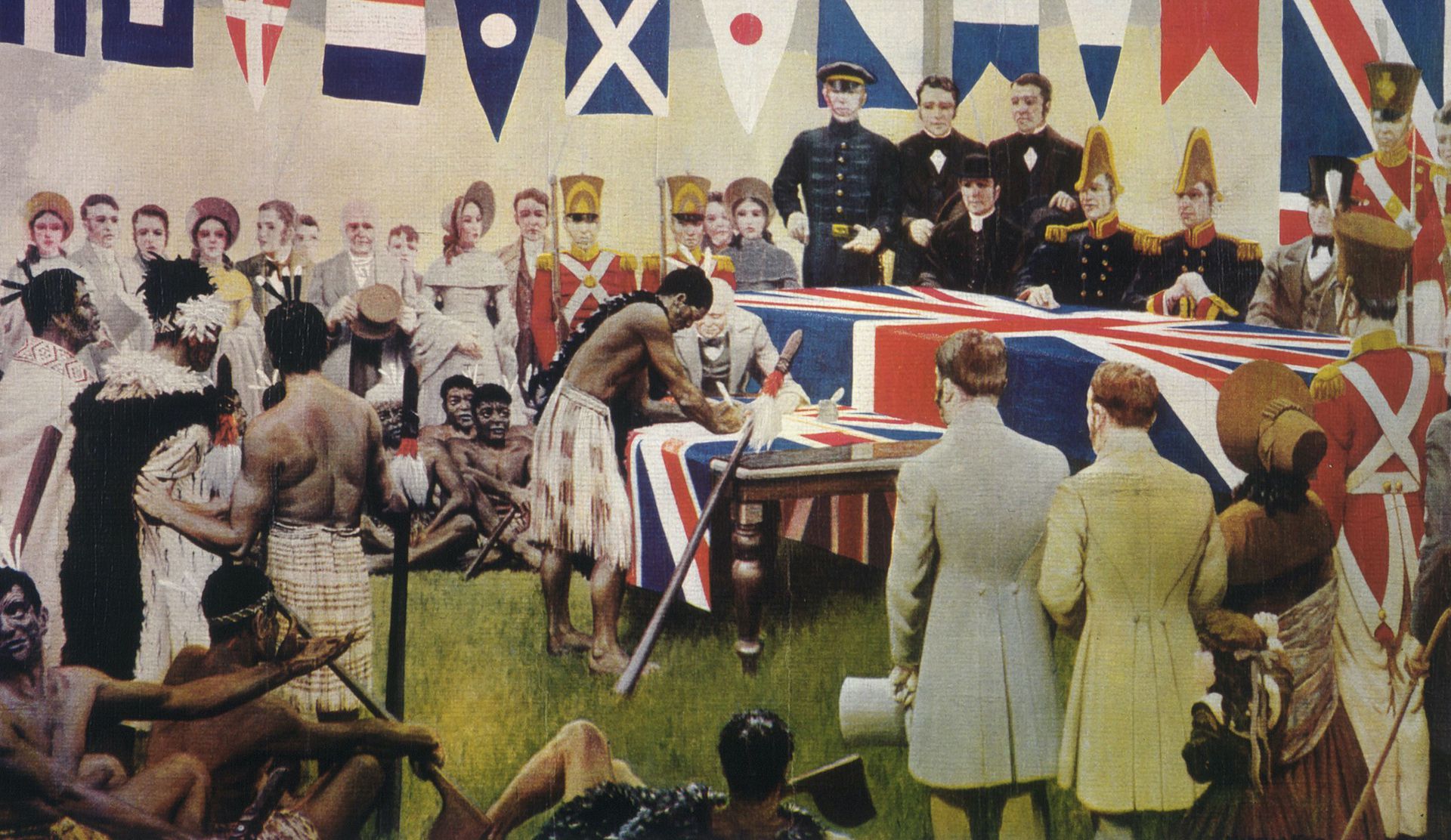

Back then, National MPs with aspirations to lead did the same. Love it or hate it. Call it “a simple nullity”, or “New Zealand’s foundation document”, the Treaty was a vital part of the country’s past – and an inescapable feature of its future.

Watching Luxon being interviewed in one of his palatial living rooms, this political commentator noted with a sinking heart the absence of bookcases – and books. Who knows, Luxon may boast an extensive library somewhere out of sight. But a public man, a man with aspirations to lead his country, should at least make an effort to reassure his fellow citizens that he does, occasionally, open a serious book or two.

In this age of Zoom, it is rare to encounter a major public figure who does not choose to be interviewed against the backdrop of his bookshelves. He, or she, knows that their viewers will be squinting to see what is there – peering through the window of their leader’s reading material – and into a part, at least, of his mind.

And, if there is no time for reading, then, at the very least, Luxon should seek out the company of those who do. An hour or two in the company of New Zealand’s Treaty “Dames” Claudia Orange and Anne Salmond, or listening to historians Vincent O’Malley and James Belich, just might open his mind to just how important this rat-nibbled piece of parchment is going to be to the way New Zealand treats itself over the next few years.

Needing a little tutoring is nothing to be ashamed of. After all, Alexander the Great was tutored by Aristotle. And you can’t say that his pupil’s impact on the world was lessened by a firm grasp of the rudiments of philosophy and history. One might even say they helped him to shape it. As Aristotle wrote: “The wise man is he who knows that he does not know”.

If he is to be an effective Prime Minister, Luxon needs to understand the Treaty and what it means to a fair percentage of the people seated in the House of Representatives. Not only that, he needs to get up to speed on Māori nationalism – if only because his coalition partners are, on this issue at least, so very far ahead of him.

Since the 1970s, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters has watched the evolution of Māori nationalism and its fluctuating attitudes towards Te Tititi – from tThe Treaty is a Fraud” to, “Honour the Treaty” – with ever-increasing alarm. Not the least of his concerns was the secret alliance that took shape 40 years ago between radical tangata whenua and “sickly white” Pakeha liberals and leftists.

Peters has always understood that the intention of these groups was never to win over a majority of the population, but to embed their decolonial ideology at the pivot-points of judicial, political, bureaucratic, academic and media power. Whatever else Peters might be, he is a convinced democrat. The leader of NZ First knows a top-down, authoritarian agenda when he sees one.

And Act leader David Seymour, you may be sure, has bookcases full of all manner of weighty tomes. He is a libertarian intellectual who bridles at anything that smacks of historical hocus-pocus, and who reaches for his metaphorical revolver whenever he senses that either the commercial marketplace, or the marketplace of ideas, are under threat from individuals and groups determined to push their thumbs down heavily on the scales of economic and personal freedom.

Seymour strongly suspects that political and economic jiggery-pokery on a truly massive scale is being attempted under the korowai (feather-cloak) of Te Tiriti – and he is not about to sit idly by while it happens.

In her ground-breaking series of essays Maori Sovereignty, Donna Awatere wrote, shrewdly, that: “The strength of white opposition will be allayed by the fact that Maori sovereignty will not be taken seriously. Absolute conviction in the superiority of white culture will not allow most white people to even consider the possibility.

Those words could have been written for Luxon. Surrounded by First Nation activism in Canada, soap powder got in his eyes. As CEO of Air New Zealand, “decolonisation” and “indigenisation” seem to have been regarded as mere marketing ploys.

The idea that the Treaty of Waitangi, and all it represents, may become the dominant issue of his prime-ministership – or that it could very easily limit his leadership to three years, or less, would appear, until this past week, to have been a possibility he has never even considered.

Well, Prime Minister, it’s time to wake up, smell the coffee, and read a serious book, or two. Or, better still, Luxon, have a good long chat about the Treaty with New Zealanders who take it very, very, seriously indeed.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you