"While the Māori King's hui was a strategic success,” opines angry left-wing blogger Martyn Bradbury, “it was a tactical failure.”

Bradbury’s observation is wildly out-of-step with the judgement of his fellow “progressive” journalists/commentators – nearly all of whom declared the King’s hui an unqualified success. So, why is Bradbury so disappointed? Not enough biff, apparently.

“There was no declaration made to force National to dump Act’s race war inciting redefinition of the Treaty Principles as the Māori King pulled his punches with a simple, ‘Be Māori’ message.”

According to Bradbury, this genuine pearl of Kingitanga wisdom “won’t blunt Act nor allow the tsunami of racism that is about to explode by allowing Act to metaphorically burn crosses across the nation".

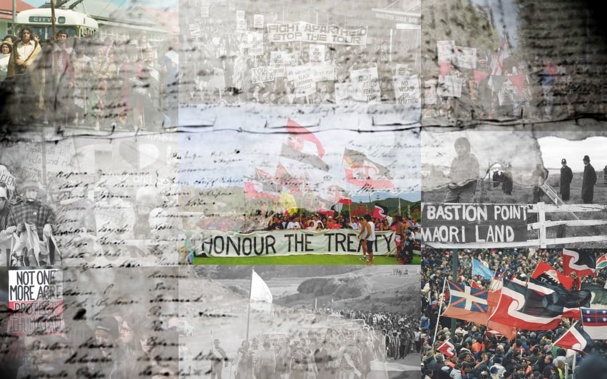

Which is actually the precise opposite of what happened on the Turangawaewae marae. Kingi Tuheitia’s gathering, its sheer size and optimistic vibe, not only blunted Act’s efforts, it probably scuppered them altogether. The 10,000+ people who answered the King’s summons forcefully reminded Pākehā of the most inimitable and irreplaceable element of the nation called New Zealand/Aotearoa – its indigenous people.

This is not new. For many years, the country’s most influential left-wing publication was The Māoriland Worker. New Zealand servicemen, on their way home at the end of World War II, wept silently when recordings of Māori songs were played on their troopship’s PA system.

Even then, New Zealanders understood that this was what distinguished them from the Canadians, Americans and Australians – their relationship with the extraordinary people with whom they shared these lonely islands at the bottom of the world.

The King and his advisers, bowled over by the thousands that descended upon Ngāruawāhia, realised that when Pākehā took in the meaning of what they were witnessing, then they would respond in much the same way as those demobilised Kiwi soldiers. The Māori would clinch their case not through intimidation and violence, but simply by being what they have always been – the heart and soul of New Zealand.

National’s Minister of Māori Development, Tama Potaka, clearly came to the same conclusion. Not only could he see that Act’s political scheme was never going to fly – there simply isn’t enough “lift” in the electorate to get David Seymour’s referendum off the ground – but also that if National sought electoral validation for canning it, then it would be given, and at Act’s expense. Most especially if people started burning crosses – metaphorical or otherwise.

The writing was on the wall for the cross-burners when Julian Batchelor’s 2023 “Stop Co-Governance” tour of New Zealand consistently failed to fire. Instead of the angry “silent majority” turning out in droves to defend democracy, Batchelor seldom spoke to more than a few score of supporters, who were, as often as not, outnumbered by the pro-co-governance protesters outside.

That the people inside the meeting halls were mostly old and white, and the people outside young and brown, was a telling sign of things to come. Batchelor was hoping to fill the Auckland Domain on the eve of the 2023 General Election. In the end, however, it was the Māori king who turned out the numbers.

But, before Tuheitia, there was Winston Peters. It was Peters and his NZ First Party that robbed Act of the numbers it needed to strap National over its radically revisionist Treaty barrel. It was Peters, too, who reassured those voters growing increasingly edgy about the “decolonisation” and “indigenisation” of New Zealand, that, with himself and NZ First in the final mix, they could be hopeful of a solution that included neither burning crosses, nor a full-on Māori nationalist revolution.

Much now hinges on the shape of the compromise Peters and his colleagues are able to fashion. As a consummate parliamentarian, the NZ First leader will be looking to give effect to Seymour’s entirely reasonable determination to have the legislature define the meaning of the te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Peters is quite aware (as many other participants in this debate are not) that legislative initiatives relating to te Tiriti are not subject to the entrenchment provisions currently protecting voting rights, parliamentary terms, and the like. Bluntly, National, Act and NZ First do not need a 75 per cent majority, or a referendum, to do what Geoffrey Palmer should have done 40 years ago – allow the House of Representatives to define “the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi”.

Peters, with Christopher Luxon’s support, can put it to Seymour that if all three members of the Coalition Government commit themselves to enabling the people of New Zealand to define the meaning and purpose of te Tiriti, distilling the essence of their endeavours into a government bill, then there is nothing to prevent them doing what Mickey Savage did in relation to his 1938 social welfare legislation – have it come into force after the next election. The opponents of te Tiriti revision will find it difficult to convince New Zealanders that they should not be permitted to render their collective political judgement in the polling booths.

Some will try. Treaty “expert” Dayle Takitimu, who had been allotted a prime speaking slot at Turangawaewae on January 20, told RNZ’s Morning Report on Monday, January 22, that she did not believe New Zealand as a whole was ready for a debate on the principles of te Tiriti. “And we’ve seen that even by the voting in of this government, on the back of very racist election promises”, the lawyer-cum-academic told RNZ’s Ingrid Hipkiss.

“The population needs to be ready for that discussion first. By pitching it as a debate, [it presents] the Treaty as renegotiable, when we’ve got one side of the Treaty partnership saying, ‘Actually, the words of that document suit us just fine.’”

The uncompromising stance of those who share Takitimu’s interpretation of the Crown-Māori relationship is likely to strengthen NZ First’s argument that, contrary to the claims that New Zealanders are not ready to debate te Tiriti, no enduring definition of the document can be imposed upon the nation from above. Indeed, it has been the efforts of the judiciary to do just that which has led to the present disconnect between Māori and Pākehā interpretations of New Zealand’s founding document.

Certainly, a strong determination on the part of the Coalition Government to encourage New Zealanders to participate in a broad and open-ended discussion on te Tiriti’s meaning and purpose in the 2020s, with the resulting legislation to be confirmed, or rejected, by voters in 2026, will place Labour, the Greens and Te Pāti Māori in an extremely awkward position. They can hardly argue against the Coalition Government seeking an electoral mandate for its efforts – not without repudiating representative democracy altogether.

Accordingly, the political pressure on Labour to embrace the politics of compromise will be immense. A refusal to do so would risk the party being isolated at the extreme end of te Tiriti debate – a position from which it would struggle to present itself as a serious alternative government.

By contrast, a workable compromise, thrashed out by te iwi Māori and the Coalition Government, could hardly fail to boost the latter’s chances of re-election. Such a resolution would be most unlikely to secure the endorsement of Martyn Bradbury or Dayle Takitimu, but it would certainly bring a smile to the faces of Luxon, Seymour and Peters.

And, who knows, may even elicit a gratified grin from King Tuheitia.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you