CNN- For thousands of years, the moon inspired humans from afar, but the bright beacon in Earth’s night sky — located more than 200,000 miles (321,868 kilometers) away — remained out of reach. That all changed on September 13, 1959, when the former Soviet Union’s uncrewed spacecraft, Luna 2, landed on the moon’s surface.

The Luna 2 probe created a crater when it touched down on the moon between the lunar regions of Mare Imbrium and Mare Serenitatis, according to NASA.

That pivotal, lunar dust-stirring moment signaled the beginning of humanity’s endeavors to explore the moon, and some scientists now suggest it was also the start of a new geological epoch — or period of time in history — called the “Lunar Anthropocene,” according to a comment paper published in the journal Nature Geoscience on December 8.

“The idea is much the same as the discussion of the Anthropocene on Earth — the exploration of how much humans have impacted our planet,” said the paper’s lead author Justin Holcomb, a postdoctoral researcher with the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas, in a statement.

“The consensus is on Earth the Anthropocene began at some point in the past, whether hundreds of thousands of years ago or in the 1950s,” Holcomb said. “Similarly, on the moon, we argue the Lunar Anthropocene already has commenced, but we want to prevent massive damage or a delay of its recognition until we can measure a significant lunar halo caused by human activities, which would be too late.”

Scientists have tried for years to declare a definitive Anthropocene on Earth, and recently presented new evidence of a site in Canada that some researchers believe marks the start of the transformative chapter in our planet’s history.

The idea of the Lunar Anthropocene arrives at a time when civil space agencies and commercial entities are showing a renewed interest in returning to the moon, or for some, landing on it for the first time.

And the paper’s authors argue that the moon’s environment, already shaped by humans during the beginning of the Lunar Anthropocene, will be altered in more drastic ways as exploration increases.

Humanity’s lunar footprint

Outdoor enthusiasts and visitors to national parks are likely familiar with the concept of “Leave No Trace” — respecting and maintaining natural environments, leaving things the way they were found and properly disposing of waste.

The moon, however, is littered with the traces of exploration.

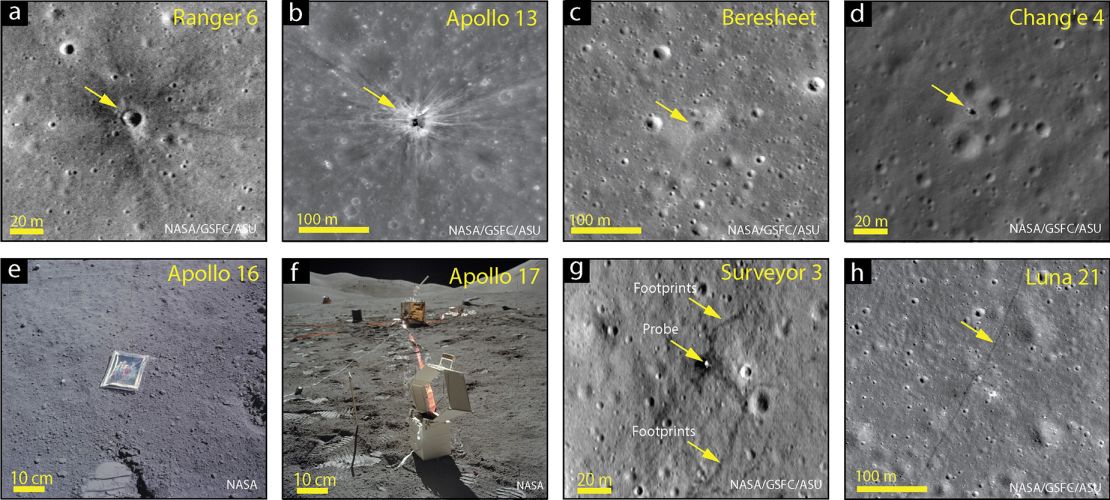

Since Luna 2’s landing, more than a hundred spacecraft have crashed and made soft landings on the moon and “humans have caused surface disturbances in at least 58 additional locations on the lunar surface,” according to the paper. Touching down on the lunar surface is incredibly difficult, as evidenced by numerous crashes that have made their mark and created new craters.

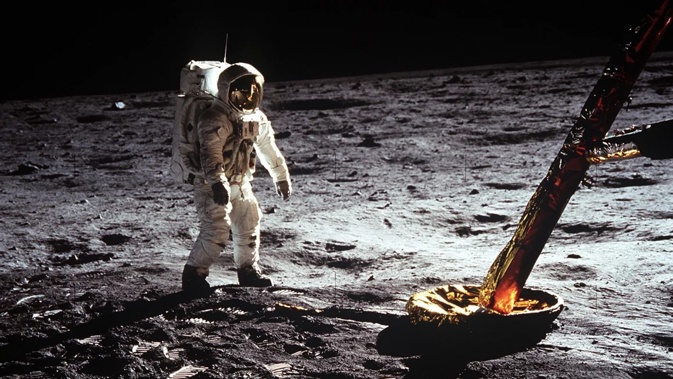

Humanity has left its mark on the moon in many ways, including impact craters left by spacecraft, lunar rover tracks, astronaut bootprints, science experiments and even family photos brought by astronauts. NASA/GSFC/ASU

The Cold War space race kicked off a series of lunar missions, and the majority since then have been uncrewed. NASA’s Apollo missions were the first to send humans around the moon during the 1960s before safely landing astronauts on the lunar surface for the first time in 1969 with Apollo 11. Ultimately, 12 NASA astronauts walked on the lunar surface between 1969 and 1972.

With the arrival of humans came a plethora of objects that have been left behind, including scientific equipment for experiments, spacecraft components, flags, photographs, and even golf balls, bags of human excrement and religious texts, according to the paper.

From Earth, the moon appears unchanged. After all, it doesn’t have a protective atmosphere or magnetosphere like our life-sustaining world does. Micrometeorites regularly hit the surface because the moon has no way of shielding itself from space rocks.

Declaring a Lunar Anthropocene could make it clear that the moon is changing in ways it wouldn’t naturally due to human exploration, the researchers said.

Astronaut Eugene A. Cernan drove a lunar roving vehicle on the moon's surface during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. It's still on the moon more than 50 years later. NASA/JSC

“Cultural processes are starting to outstrip the natural background of geological processes on the moon,” Holcomb said. “These processes involve moving sediments, which we refer to as ‘regolith,’ on the moon. Typically, these processes include meteoroid impacts and mass movement events, among others. However, when we consider the impact of rovers, landers and human movement, they significantly disturb the regolith.”

The moon also has features like a delicate exosphere composed of dust and gas and ice inside permanently shadowed areas that are vulnerable and could be disturbed by continued explorations, the authors wrote in their paper. “Future missions must consider mitigating deleterious effects on lunar environments.”

Lunar exploration frenzy

A new space race is heating up as multiple countries set their sights on landing both robotic and crewed missions to explore the moon’s south pole and other unexplored and difficult-to-reach lunar regions.

India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission made a historic successful landing on the moon in 2023 after Russia’s Luna 25 spacecraft and Japanese company Ispace’s HAKUTO-R lander both crashed. This year, multiple missions are heading for the moon, including Japan’s “Moon Sniper” lander that is expected to attempt to touch down on January 19.

Astrobotic Technology’s Peregrine spacecraft launched this week amid objections by the Navajo Nation that the vehicle carried human remains that customers paid to send to the lunar surface, sparking fresh debate over who controls the moon. But a propulsion issue noticed hours after liftoff means that Peregrine won’t be able to attempt a moon landing, and currently, its fate is uncertain.

NASA’s Artemis program intends to return humans to the lunar surface in 2026. The agency’s ambitions include establishing a sustained human presence on the moon, with habitats that are supported by resources like water ice at the lunar south pole. China’s space ambitions also include landing on the moon.

“In the context of the new space race, the lunar landscape will be entirely different in 50 years,” Holcomb said. “Multiple countries will be present, leading to numerous challenges. Our goal is to dispel the lunar-static myth and emphasize the importance of our impact, not only in the past but ongoing and in the future. We aim to initiate discussions about our impact on the lunar surface before it’s too late.”

The moon’s archaeological record

Humanity’s traces on the moon have come to be viewed as artifacts that essentially need some form of protection. Researchers have long expressed a desire to maintain the Apollo landing sites and catalog the items left behind to preserve “space heritage.” But this type of preservation is difficult to pull off because no one country or entity “owns” the moon.

“A recurring theme in our work is the significance of lunar material and footprints on the moon as valuable resources, akin to an archaeological record that we’re committed to preserving,” Holcomb said. “The concept of a Lunar Anthropocene aims to raise awareness and contemplation regarding our impact on the lunar surface, as well as our influence on the preservation of historical artifacts.”

An astronaut's boot left an impression on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. NASA/JSC

The Apollo 11 lunar landing marked the first time humans set foot on another world. The footprints left in the lunar dust by astronauts are perhaps the most emblematic of humanity’s ongoing journey, which will likely include planets like Mars in the future, the researchers said.

“As archaeologists, we perceive footprints on the moon as an extension of humanity’s journey out of Africa, a pivotal milestone in our species’ existence,” Holcomb said. “These imprints are intertwined with the overarching narrative of evolution. It’s within this framework we seek to capture the interest of not only planetary scientists but also archaeologists and anthropologists who may not typically engage in discussions about planetary science.”.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you