A groundbreaking, home-grown cancer therapy trial just hit another milestone and there are hopes to bring it to Kiwis, writes Jamie Morton.

Michele Leggott remembers the morning of February 8, 2023, with crystal clarity.

The prominent Auckland poet sat trembling in a tiny clinical office on the seventh floor of Wellington Hospital, with husband Mark by her side.

The doctor ran through some quick questions about her sleep and diet, then cut to the chase.

“We’re looking at a PET scan you did yesterday, and there is no active lymphoma,” he told her with a laugh.

“You are in remission.”

As Leggott burst into tears, a young research student in the room scrambled for the nearest box of tissues.

It was a surreal moment: just like the day, not much more than a year before, she’d been given only a year to live.

Often treatable, her non-Hodgkin’s diffuse large B-cell lymphoma had been first considered a “good cancer” to have.

But chemotherapy and radiotherapy didn’t work, nor did a stem cell transplant.

When her haematologist offered her a last chance, with a referral for a new and curious type of treatment she’d never heard of, Leggott leapt at it.

“There was literally nothing to lose.”

Rewind to late 2019.

In Wellington, a team of clinicians at the Kelburn-based Malaghan Institute of Medical Research, began enrolling patients for the first trial of its kind in the country.

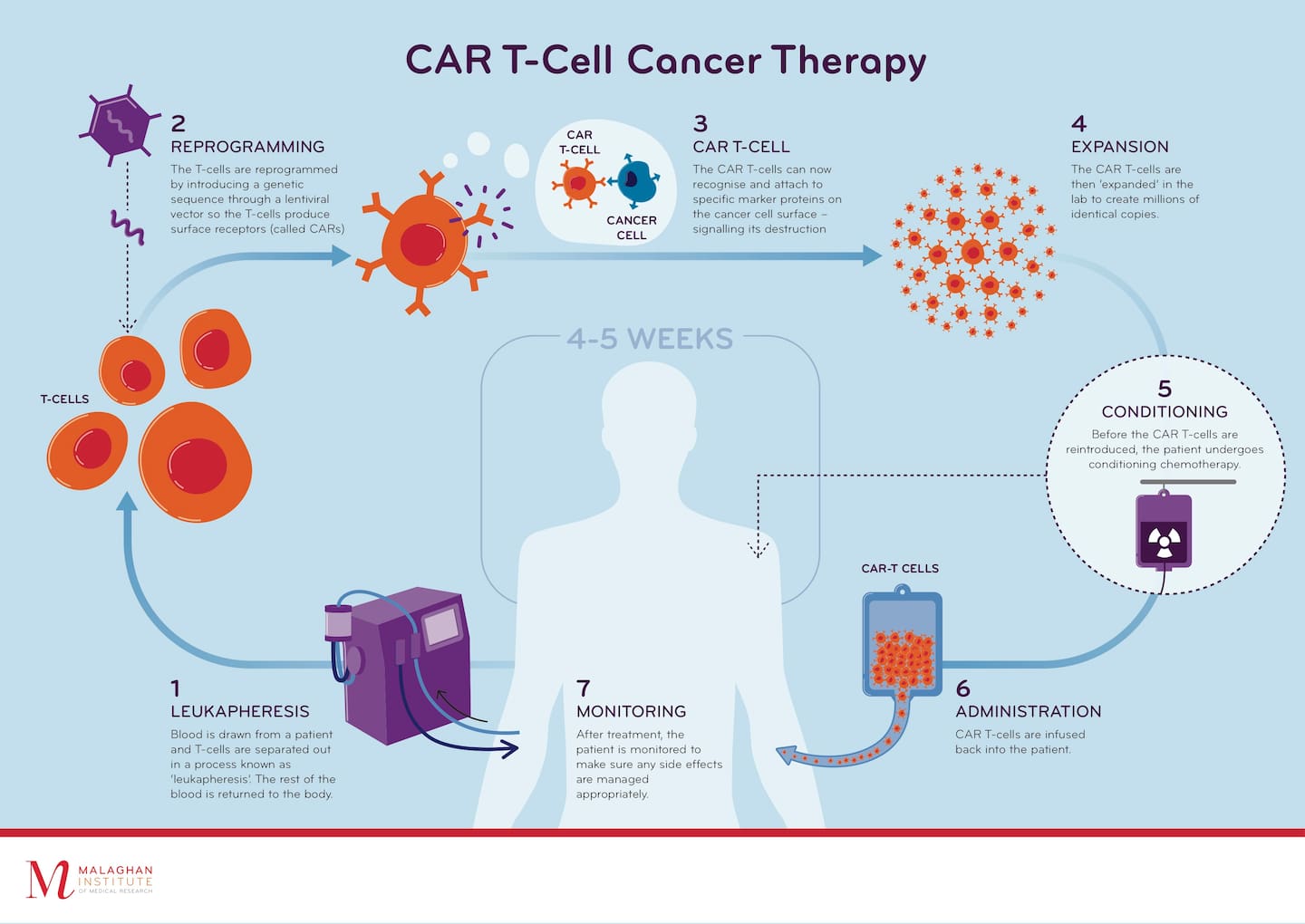

It involved what’s called CAR-T cell therapy, in which a patient’s immune cells are collected, genetically modified to recognise and kill their cancer, then given back to them as treatment.

Source / Malaghan Institute

By that point, it was already being used overseas to combat some forms of cancer like lymphoma, leukaemia and for myeloma.

Some desperate Kiwis, including businessman and comedian David Downs, had been forced to go offshore to access it.

The scientists behind the Wellington trial, dubbed Enable, however suspected they’d found a therapy that could well compete with international products.

Its promise had been revealed in a research collaboration between the institute and China’s Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health.

From there, researchers had tweaked the manufacturing process to make a new product, while lab studies turned up small changes that could slash the risk of side effects brought on by over-stimulating the immune system.

Leggott was among 21 Kiwi patients, all of whom had run out of options, recruited for the phase 1 trial.

Just three months after her cells were collected in September 2022, hand-made CAR T-cells were waiting for her to be infused.

“The infusion itself was extremely straightforward and I didn’t have any side effects afterwards.”

When the preliminary clinical data came back, Malaghan clinical director Dr Robert Weinkove and his team had much to be pleased about.

Malaghan Institute clinical director Dr Robert Weinkove. Photo / Supplied

Their results, reported to a major US conference late last year, found fewer side effects and “very promising” effectiveness.

Around half the participants’ lymphomas were found to be in complete response – or clear of cancer – just three months after receiving the therapy.

Last week, it was announced another nine patients have completed treatment. Their results were due to be revealed in June, but indications were positive.

Meanwhile, the trial has drawn international attention - and India-based pharma giant Dr Reddy’s Laboratories signed up for a multi-million-dollar deal last year.

Momentum had also picked up with scientists using a new automated process for clinical production of the CAR T-cells, while foundations were laid for a phase two trial involving 60 patients.

“We would like to enrol and treat the patients in two years,” Weinkove said.

For New Zealand, he said the possibility of delivering an effective and comparably safer treatment was exciting.

Even in the US, only a quarter of patients eligible for CAR T-cell therapy received it.

That was because of its high cost, but also the logistical headache of giving the treatment and monitoring for side effects.

“If we can combine the effectiveness of CAR T-cell therapy with fewer side effects, we can make the treatment cost-effective and deliverable in New Zealand’s health system,” he said.

“This means more patients could benefit from this one-off, outpatient-based treatment.”

Malaghan Institute researchers are trying to find a CAR-T cell therapy more effective than current ones – but also safer and more affordable – that can be introduced to our healthcare system. Photo / Supplied

He saw potential to push the tech itself further: whether by improving the therapy’s safety profile and effectiveness, or widening its reach to other subtypes of lymphoma and myeloma.

As for whether it could work against those more commonly diagnosed “solid” cancers, like lung, breast and prostate, prospects weren’t as promising.

“It seems that for solid cancers, additional changes to the CAR T-cells might be needed to help them recognise the cancer cells, or to prevent them from becoming exhausted.”

Professor Chris Jackson, a leading oncologist who served six years as the NZ Cancer Society’s medical director, expected that, for now, CAR T-cell would stay a “relatively small but important area of cancer therapy”.

“But it’s something that we just have to do in New Zealand, because if we don’t, we won’t have the infrastructure to deliver it - and we’ll be left a long way behind.”

Collectively, the type of cancers targeted by the new therapy represented the sixth most common malignancy in New Zealand – or about 1600 diagnoses each year.

Because most patients still responded to conventional therapy, Weinkove estimated that around 200 Kiwis could annually benefit.

“Although not every patient’s lymphoma responded, over half did, and some patients remain in life-changing complete remissions that have lasted for years so far – and that we hope will continue indefinitely,” he said.

Poet Michele Leggott and her husband Mark Fryer. Photo / Sylvie Whinray

“This has allowed some trial participants to return to work, care for their children or grandchildren, and get on with their lives.”

For Leggott, the difference was life and death.

“It’s quite simple: if I hadn’t been able to access CAR-T, I wouldn’t be here now.”

With a single, 4.5ml infusion of her own tweaked cells, her body was able to fight off cancer in just 12 weeks.

She’s well and hasn’t needed treatment since.

“If CAR-T cell therapy can work for a severely depleted metabolism like mine was, imagine what it might be able to do for someone experiencing their first relapse,” she said.

“Everyone needs to know about this therapy and its possibilities. Everyone has lost family or friends to cancer.

“Perhaps that doesn’t have to happen so often in future.”

Jamie Morton is a specialist in science and environmental reporting. He joined the Herald in 2011 and writes about everything from conservation and climate change to natural hazards and new technology.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you