An Ōtorohanga man died while on the waiting list for triple bypass surgery. Nicholas Jones investigates.

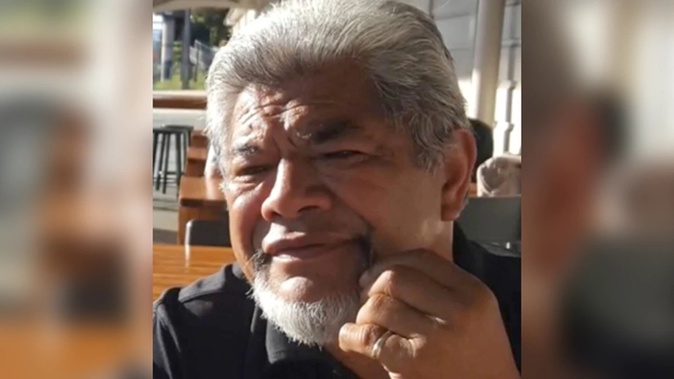

Gerry Te Kare was nearly done mowing the lawns when his heart stopped.

His wife, Pauline, gave CPR until paramedics and the fire brigade arrived. After the fifth shock from a defibrillator, a faint heartbeat was detected.

Te Kare, 68, was put in an induced coma and flown from Ōtorohanga to Hamilton's Waikato Hospital.

The family held on to hope, but he never woke up; his brain had been starved of oxygen for too long. Life support was removed and he died on January 16 last year.

Doctors expressed sympathy but also frustration, the family says. That's because Te Kare was overdue for triple bypass surgery.

"When he arrived on the chopper the anaesthetist questioned, 'What's this guy doing here? He should have had his operation,'" Pauline says. "Another specialist said the same thing."

The family is speaking out after reading an ongoing Herald investigation that revealed Waikato's cardiac surgery department was overhauled through 2019 and 2020 after a host of problems including how waiting lists were managed.

Hundreds of cardiology patients were caught in delays, and some got so sick while waiting they had to be rushed to hospital for emergency treatment.

Waikato DHB says the cardiac surgery problems were fixed and waiting lists were "relatively low" before the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown, but demand for urgent, life-saving procedures greatly increased in the months afterwards.

Elective surgery delays around the country are again worsening as procedures are postponed to allow the redeployment of hospital staff to treat Omicron cases. Nearly 25,000 Kiwis were already overdue treatment in January, the latest available figures show.

Te Kare's whānau don't want others to be put in the same situation.

"The machine was breathing for him," Pauline says. "We had that last hope that when they turned it off, he would come through. But it didn't happen."

Gerry and Pauline Te Kare fell in love after meeting at a hui for Māori local government workers. Photo / supplied

'We were just waiting for the call'

Heart disease was discovered after Te Kare had a routine check-up in May 2020. His bus driver's licence was cancelled, which was a blow to the family income.

"He was the type that didn't sit around if there was work to be done," Pauline says.

That work ethic was instilled as one of nine children raised in a strict Mormon household in Ōtorohanga. Later in life, he was living in Auckland when he met Pauline at a hui for Māori local government workers.

They'd both been married before, and Te Kare had two adult children. After the couple wed, they moved to Ōtorohanga where Te Kare, a panel beater and truckie by trade, drove the school bus and ran the yard, employing a gruffness that silenced rowdy kids and concentrated the minds of colleagues.

"Everybody in the valley knew who he was," says Pauline. "If you ever did anything wrong, he would let you know. But once he said it, that was it. He was a very fair person. And he would be the first to help you out if ever you were struggling."

After his heart condition was discovered, he passed the required pre-assessments for bypass surgery and then waited. And waited.

According to Waikato DHB, he should have had his surgery within 90 days, "however, due to the high acute demand" he'd waited 115 days. That indicates Te Kare was added to the waiting list in September, about four months after his check-up.

"We were just waiting for the call," Pauline says. "He would ask, 'When is it going to happen?'"

Te Kare minimised his activity but still did some jobs around the house.

"We were doing the lawns together," Pauline says of when he went into cardiac arrest.

"I was on one side of the lemon tree, and he was on the other. I didn't know he had collapsed."

It was an excruciating decision to remove his life support. The pandemic meant whānau in Australia couldn't fly back.

Waikato's cardiac surgery department was overhauled through 2019 and 2020. Photo / Alan Gibson

A secret review

The Herald began investigating Waikato Hospital in December 2019 after learning of an independent review into problems in cardiac surgery.

In January 2020 Waikato DHB refused a Herald request under the Official Information Act for a copy of the report. That decision was appealed to the Ombudsman, and after the watchdog's intervention the DHB in February last year released it, but redacted all but some introductory comments, citing privacy.

However, the Herald obtained a full copy of the report, which was completed by a team of Australian experts, including leading surgeons and critical-care specialists and nurses.

Their November 2018 findings were scathing – describing an understaffed and "broken system" that had contributed to "concerning outcomes for patients".

Bullying and oppressive behaviour was "prevalent at all levels of the organisation", the report found, with staff "struggling to survive in the current environment and [who] are calling out for resources, an effective leadership and interdepartmental collegiality".

Much of the findings were concerned with how surgery waiting lists were handled. The structure for referring patients to cardiac surgery was "monopolised and exclusive", the reviewers warned: "This must change as a matter of priority as it is adversely affecting patient safety and maintaining interdepartmental conflicts."

Handling of cardiothoracic operating lists was "grossly dysfunctional", the reviewers concluded, and more transparent reporting was needed, including of waiting-list times and deaths.

Staff told them of "a real inertia to change" and that "patients' needs were of a lower priority than those of some staff".

As a result of the findings, the DHB undertook a two-year overhaul of its cardiac surgery service including hiring more staff and changes to improve teamwork, governance and leadership. It says no patients were harmed as a "direct consequence" of the problems, and some of the review's claims weren't backed by evidence.

Subsequent reporting by the Herald revealed delays stretched back to at least 2016, and that by late 2019 the ministry was worried about large waiting lists in Waikato's cardiology services, a related but separate department.

Documents show that in August 2020, Lakes DHB, which covers Rotorua and Taupō and sends heart patients to Waikato, told the ministry it was worried about cardiac surgery and cardiology delays, "including minimal access to waiting-list information, and poor communication with clinicians regarding patients waiting".

"The long waiting lists lead to acute hospital admissions and bed block, avoidable investigations being repeated, and poor patient outcomes," the DHB warned.

The Herald revealed the cardiac surgery overhaul in a front-page article in April 2021. Photo / file

'In the proverbial'

Waikato DHB, the ministry - which monitored progress after the 2018 review - and Lakes DHB all say the situation significantly improved, including because more staff were recruited and an extra catheter lab opened.

However, emails newly obtained by the Weekend Herald show as recently as last September cardiac services were under stress because of high demand.

Patients often recover from heart surgery in intensive care, and high demand meant Waikato couldn't send ICU nurses to help with Auckland's Delta outbreak response, unlike other major DHBs.

"Seems Waikato are in the proverbial re cardiac," Dr Andrew Connolly, head of department of general and vascular surgery at Counties Manukau DHB, wrote to colleagues about why no reinforcements were likely.

A Waikato DHB spokesperson says it "disagrees with the language used in the emails you reference", but "there was certainly a challenge of high acute demand, which the DHB was able to meet by retaining our full staffing levels".

As of the end of February, five cardiac surgery patients were waiting longer than four months for a procedure.

However, cardiology waiting lists remain a problem: 184 people were waiting longer than four months for a first specialist appointment, and 158 waited beyond that time frame for a procedure.

The cardiology waiting list had been almost cleared after backlogs caused by the 2020 lockdown, the DHB says, but grew again after last May's cyberattack, and subsequent Covid disruption.

A fourth catheter lab has opened to meet demand, and another lab is being upgraded with more efficient equipment and will be fully operational by June.

"We have considerable experience now in addressing backlogs caused by major events, including Covid-19 lockdowns, and would expect to introduce similar plans once staffing levels and hospital capacity return to more normal levels [after the Omicron wave]," the DHB spokesperson says.

They declined to comment further on Te Kare's care, citing privacy, but said in September and October 2020 the hospital did up to three times the normal levels of acute cardiac surgeries.

"Where there are periods of high acute demand it is likely to impact theatre access for elective procedures. This is never ideal but it is appropriate that patients should be prioritised according to clinical recommendations."

An extra specialist has been appointed to monitor people waiting for surgery, the spokesperson says, and identify any who needed urgent treatment.

Hospitals are diverting staff and resources to treat Covid-19 patients. Photo / supplied

Covid delays

The latest available national figures show in January 24,702 patients were waiting longer than four months for treatment – a 25 per cent increase since September 2021, the month after the level 4 lockdown.

DHBs have used extended hours, weekend lists and outsourcing to private hospitals to keep services going, a ministry spokesperson says, but hospitals with large numbers of Covid patients are having to cut regular services to cope.

"This will be dependent on case numbers and the strategies individual DHBs have in place to deal with a surge in case numbers, and therefore the effects are difficult to quantify at this stage."

Heart patients are among those to have had procedures put off. Those affected include Clive Caine, 70, who in January went public in the Herald after his triple bypass surgery at Auckland City Hospital was deferred, despite doctors having told him he was at risk of dropping dead.

Eventually, Auckland DHB paid for the operation to be done privately which, after more delays, happened about three weeks ago.

"By that time I had been nearly five months on the waiting list," says Caine, who'd had two heart attacks before being accepted for surgery last October. "You didn't know if you would wake up in the morning."

Another area under pressure is eye services. DHBs worried about people losing sight while caught in delays after the 2020 lockdowns and, with waiting lists again lengthening, hospital ophthalmologists warn "the outlook is bleak".

"Across the Auckland and Waitematā District Health Board eye service there are an estimated 6000 overdue follow-ups," says Dr Peter Hadden, chairman of the New Zealand branch of the Royal Australian and NZ College of Ophthalmologists.

"This is triple the number from two years ago."

Gerry Te Kare's family are private people but are telling his story in the hope it will improve services and save others from similar loss.

They are full of praise for the "fantastic" DHB staff but worry the system isn't coping.

Pauline's daily walk now includes Ōtorohanga Cemetery. She sits by her husband and fills him in on the latest news and gossip, and complains about the odd jobs – a leaky tank, car repairs – that he used to take care of so well.

"I think of how he didn't get the surgery," she says. "That he might still be here if he had."

- by Nicholas Jones, NZ Herald

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you