Tom Irvine from Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei kicked things off. “What a wonderful day to celebrate such a boring machine,” he said. “I’ve been saving that up since 2019.” No rain in sight.

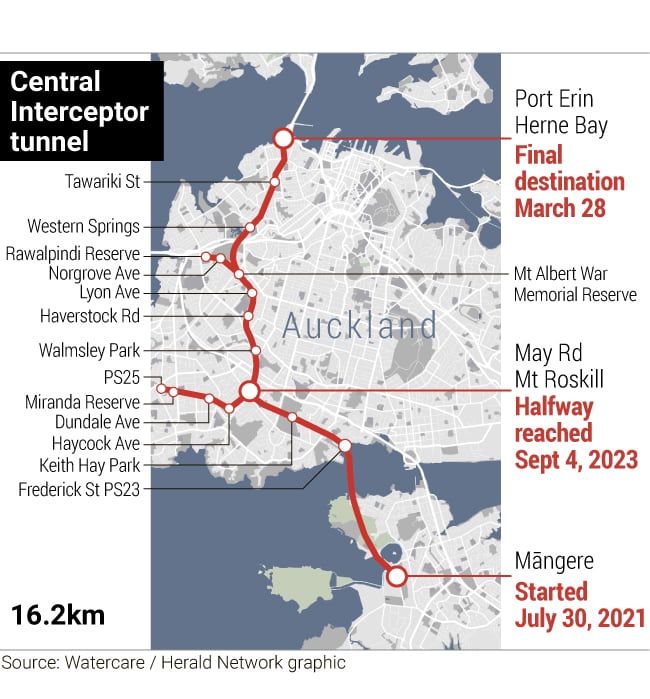

The boring machine (TBM) Hiwa-i-te-Rangi, named for a Matariki star, is Watercare’s 200m engine with a revolving diamond-head cutter. On Friday, it broke through the last section of a new 16.2km sewage tunnel from Māngere to Herne Bay. A celebration was held at the end point in the park at Point Erin.

The Central Interceptor project will carry waste from the Auckland isthmus to the treatment plant on the south side of the Manukau Harbour. And the TBM has now finished its work.

The tunnel is large enough for a giraffe to stand up in, although such a thing is unlikely. It runs 110 metres beneath the Hillsborough ridge and less than 15m under the seabed. It’s the longest continuous tunnel yet built by Watercare’s European construction partners, Ghella Abergeldie Joint Venture.

Watercare chief infrastructure delivery officer Shayne Cunis spoke at the celebration.

Shayne Cunis from Watercare: "We're changing a city." Photo / Michael Craig

Shayne Cunis from Watercare: "We're changing a city." Photo / Michael Craig

“For seven years minus 23 minutes, this has been my life,” he told the crowd of 250 tunnellers, Watercare staff and city dignitaries. And he was not kidding: Cunis had open-heart surgery during the project and, legend has it, his first words after surgery were “How’s the tunnel?”.

At the ceremony he looked like a tired and happy man.

“I wore red today,” he said, referring to his t-shirt, “because Italy is synonymous with two things: tunnelling and Ferrari.”

“Sorry for mentioning Formula One,” he added. “I know that’s a bit contentious at the moment” — referring to this week’s demotion of New Zealand driver Liam Lawson.

“We’re changing a city,” Cunis said. “We’re fixing over 100 years of degradation. The spine of the new sewage system is in.”

The Māngere treatment plant was the brainchild of former mayor Sir Dove-Myer Robinson. He moved sewage from the central city and got it properly treated. But many of the old pipes pre-dated him by generations and when the rains come, sewage spills onto the beaches.

The Māngere treatment plant was the brainchild of former mayor Sir Dove-Myer Robinson. He moved sewage from the central city and got it properly treated. But many of the old pipes pre-dated him by generations and when the rains come, sewage spills onto the beaches.

By the time the project is fully completed in 2028, it will contain 80% of current wastewater overflows. That will mean much cleaner beaches, not just around the central city but, thanks to tides and currents, up the east coast bays of the North Shore as well. And it’s future-proofed for growth.

“This,” said Cunis, “is real city building.”

Speaking with the Herald, he said thatin his view, it’s not a new stadium the city needs, it’s more tunnels.

Mayor Wayne Brown told the crowd it was part of his election promise in 2022, to “fix and finish what we’ve started”.

Mayor Wayne Brown underground with workers on the Central Interceptor. Photo / Michael Craig

Mayor Wayne Brown underground with workers on the Central Interceptor. Photo / Michael Craig

The project has come in on time, on budget, and despite the difficulties of Covid. It has also been a safe project, with no serious injuries.

Watercare is proud of that, and so is Brown, who was always keen to make sure it happened.

But “fix and finish” also recognises that someone else started it. No one at the ceremony mentioned who that was. In 2019, then-mayor Phil Goff got council agreement to bring the project forward by 10 years, when it wasn’t meant to start until the end of this decade.

The projects we need, changing the city as, Cunis says, and we’ll forget they’re even there.

It was hot and humid, but despite Irvine’s pleasure at the day, a dark grey sheen of rain moved slowly in from the west, beyond the giant macrocarpas and pōhutukawa of the park. Opera singers Lilia Carpinelli, originally from Naples, and Ridge Ponini, from the Cook Islands, sang Puccini’s Nessun Dorma, from Turandot.

The great Luciano Pavarotti sang this aria at the 1990 Football World Cup in Italy, making it popular for public occasions of all kind. Why not a sewage system built by Italian tunnellers? It seemed totally right and it was very beautiful. The aria calls for a high-toned, ringing tenor, and Ponini was bang on.

Nessun dorma means “let no one sleep”, and that’s been their mantra with this project: 12-hour shifts, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Ridge Ponini and Lilia Carpinelli singing at the breakthrough ceremony for the Central Interceptor. Photo / Michael Craig

Ridge Ponini and Lilia Carpinelli singing at the breakthrough ceremony for the Central Interceptor. Photo / Michael Craig

The project created 600 jobs, filled by people of 40 different nationalities. Many of the New Zealanders among them have skills they didn’t have before. Many of those from overseas are staying on: there’s more water-services tunnelling to be done in other parts of the city, and other tunnelling infrastructure, too.

“We want that tunnel under the harbour,” one Italian worker told the Herald later, as we waited to go underground in a yellow metal cage. “Tunnels last much longer than bridges, you know.”

ABOVE GROUND, Mayor Brown gave the ceremonial order to start the TBM on its final bit of work. “Ready, go!” he shouted, and up on the big screen we watched the rock wall, which didn’t move.

A call-and-response haka started up from the Watercare people in the crowd.

Hei rungaheiraro / Hīhā, hīhāTōiamai / Te Waka Ki teurunga / Te Waka Ki temoenga / Te waka, ki tetakotorangatakoto ai ite waka!

Watercare workers perform a haka as Hiwa-i-te-Rangi breaks through. Photo / Michael Craig

Watercare workers perform a haka as Hiwa-i-te-Rangi breaks through. Photo / Michael Craig

Little bits of rock fell away but the rockface itself didn’t move and the haka didn’t let up. Two tunnellers on a scaffold above us leaned over, peering intently into the enormous hole where, 30m below, the TBM would push through. Heads down, motionless, it was as if they were praying.

Then, a small hole, high on the wall, and beyond it in the gloom, we could see the cutterhead turning. It was like looking into the lair of a monster. A taniwha, a minotaur, an alien. More holes appeared, and the haka stepped up a notch. Suddenly, a slab of the wall fell away, and another, and then the wall was down.

Above ground, jets of flame roared into life. Below, the whole cutterhead was now visible, rotating slowly to a stop.

Deputy Mayor Desley Simpson celebrates with Mayor Wayne Brown and Watercare executives. Photo / Michael Craig

Deputy Mayor Desley Simpson celebrates with Mayor Wayne Brown and Watercare executives. Photo / Michael Craig

To get down to the TBM, we suited up in orange and blue overalls, pink hard hats, safety glasses and steel-capped boots, and they gave us a quick lecture in how to use the breathing apparatus if something went wrong. It seemed very complicated.

Then we gathered in a yellow metal cage, 10 at a time, a crane lifted us high in the air, swung us over the pit and lowered us down.

On this day, there were 30 or so people down there, all cheering, waving flags and banners, posing in front of the now-resting machine.

“Muchas gracias, or whatever it is,” said Mayor Brown when he rounded off the formalities. He looked at all the Italian tunnellers. “I probably got that wrong.”

He did: “muchas gracias” is Spanish. The crowd laughed; they didn’t seem to mind. It was a good day.

Then it rained. Reminding us why we need these tunnels.

Simon Wilson is a senior writer covering politics, the climate crisis, transport, housing, urban design and social issues, with a focus on Auckland. He joined the Herald in 2018.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you