- More than 33,000 cases of mild traumatic brain injury are reported in New Zealand each year – a third of them from sport like rugby.

- Scientists suspect they’ve found a way to pick up these injuries sooner, after identifying telltale build-ups of iron in brains affected by recent head knocks.

- They say their discovery could ultimately help doctors to know when to stand down players

New Zealand researchers have discovered a telltale marker left in the brain after a concussion – potentially giving doctors a clearer steer on when to stand down players.

Around 33,250 cases of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) are reported in New Zealand each year, with 20% to 30% stemming from recreation and sport like rugby.

Now researchers have found how signatures of abnormal amounts of iron in the brain could point the way to more reliable diagnosis and prognosis.

They found how a build-up of iron in the brain – which can signal damaging disruption to cells and brain tissue – occurred in the early stages of a mTBI.

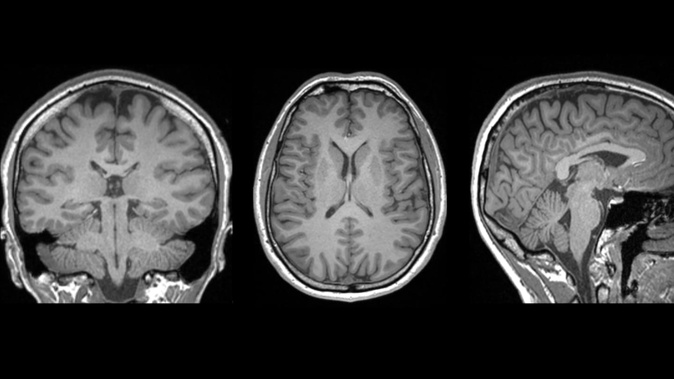

Their newly published study, led by Auckland University of Technology (AUT) researcher Christi Essex, used an advanced MRI technique to scan the brains of young males who had recently suffered head injuries.

“When we compared each athlete to a healthy population, we saw that athletes with abnormal iron accumulation also tended to have more severe symptoms, highlighting a possible link between iron levels in the brain and symptom severity,” Essex said.

Initially, a third of participants suffering from mTBIs showed these markers – but that rate rose to more than 80% when the team used a more sensitive analysis method.

Alice Theadom, a professor of brain health at AUT, said these findings marked a “very exciting discovery” that could shed crucial new light on what happens to the brain after concussion.

“Before, we had to rely on what athletes tell us,” Theadom said.

“This may potentially enable us to see much more clearly what is going on in the brain so we can provide better advice to those affected.”

Essex said the findings shouldn’t put people off contact sports.

“While this might seem like bad news, it’s actually a constructive step forward, enabling us to see what’s happening in the brain and to know when someone needs to step away from sport to let their brain recover,” she said.

“As scientists, it isn’t our goal to stop people taking part in sports, it’s to improve diagnostic tools and outcomes for individuals in our community – and this could represent a step forward in that goal.”

Associate Professor Mangor Pedersen, who supervised the project, hoped the research could lead to lasting changes in dealing with head injuries, but added that more work was needed.

“We hope studies like this pave the way for funding to collect larger control datasets,” Pedersen said.

“This would enable more robust comparison of each athlete to a healthy population and allow us to spot the more subtle changes in the brain that are characteristic of mTBI.

A player is treated for a head injury. Photo / Photosport

A player is treated for a head injury. Photo / Photosport

“With enough research, this imaging may eventually become part of standard medical practice.”

And if that happened, Essex said, then even better decision-making can take place.

“Such progress would allow for personalised recovery plans, interventions that could help athletes achieve better long-term brain health and will enable players to make their own choices about their sports participation.”

The study – a collaboration between AUT, the University of Auckland, Mātai Medical Research Institute and Duke University in the US – follows another New Zealand-led breakthrough in brain injury research.

That research used donated brain tissue, mainly from former rugby players, to show how specific cells respond to damage from repeated head knocks.

It’s taken scientists closer to understanding a disease that often results from that trauma – chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE – and linked to an accumulation of tau proteins in the brain.

While these proteins are a normal feature of the brain, in those affected by CTE, they can “tangle” in a specific region and hamper the brain’s ability to function normally.

Beyond the build-up of tau, the research team discovered that astrocytes – support cells in the brain – seem to play a pivotal role and may also be responding to free radicals generated by excess iron.

“Many of these astrocytes appeared to be responding to leaky blood vessels and trying to protect the brain from further damage,” said study senior author Dr Helen Murray, of the University of Auckland.

“This discovery points to inflammation and vascular health as promising areas for future therapeutic strategies.”

Jamie Morton is a specialist in science and environmental reporting. He joined the Herald in 2011 and writes about everything from conservation and climate change to natural hazards and new technology.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you