- Patients queue from 6am at Ōtara clinic due to long waits and problems getting bookings at other GPs.

- Tamaki Health CEO: Waiting in a queue in the cold is “absolutely heartbreaking,” urges more investment in GPs.

- High patient volumes and staff shortages at Ōtara clinic lead to doctors working on days off.

Patients in one of New Zealand’s most impoverished communities are so desperate to see a doctor they’re lining up outside in the cold hours before the clinic opens its doors.

The queue outside Ōtara Local Doctors and Urgent Care starts building from 6am, with those waiting telling the Herald that trying to secure an appointment with other GP clinics often means waiting weeks to be seen.

Even at the Ōtara clinic, which offers a walk-in service, patients said they can face lengthy delays if they’re not there early.

The clinic is owned by Tāmaki Health and its chief executive, Lloyd McCann, described the situation as “absolutely heartbreaking” and “gutting”

The clinic’s community liaison manager, Lorenzo Kaisara, said the queue had progressively got worse in the five years he’d worked there.

“The line just gets greater and greater even in the cold which breaks my heart. To see my people sitting out here and you’ve seen the majority who are in the cold before seven o’clock are Māori and Pacific,” he said.

“They are already sick. They get more unwell sitting out here in the cold”.

Dressed in a thick winter dress, puffer jacket and scarf, Toa Salaina, 44, arrived when it was still dark with her own chair to make the wait on the pavement more comfortable.

“I really want to see the doctor about my pain in my back,” she said.

The Ōtara clinic’s walk-in option means no appointment is necessary.

“If we book the appointment and we are enrolled with another GP, they tell us it is full. That’s why we like to come here.”

However, Salaina said staff are so overrun that unless you arrive early, the wait to see the doctor can be up to five hours once inside.

“That’s why we need the Government to help, to add some more nurses and doctors to help the people.”

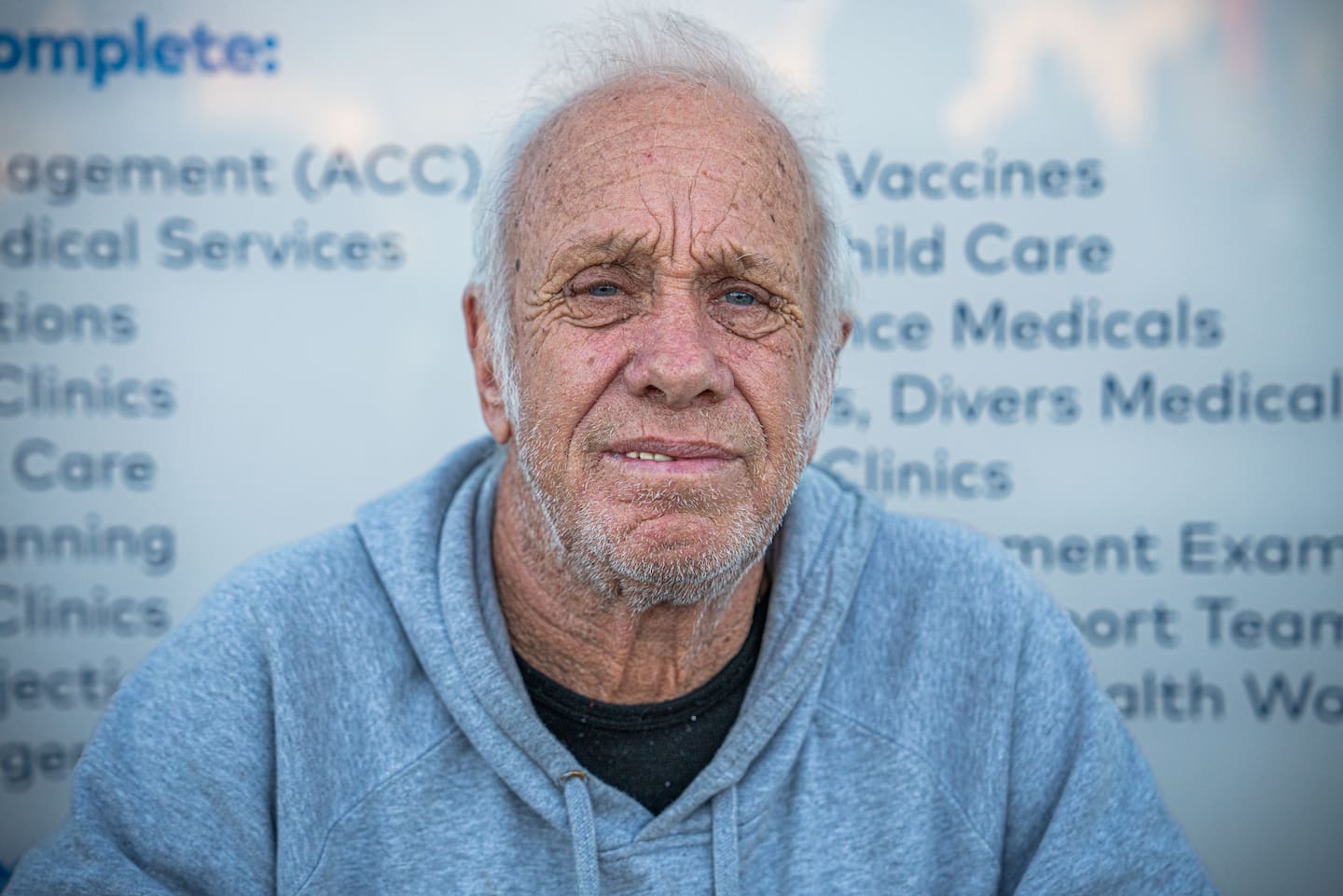

Greg McIndoe, 66, arrived at the clinic with a walking frame and hobbled towards the queue. He’d recently had knee surgery and was in pain.

He said it was “outrageous” people had to line up in the cold to get care.

Around 20 people, including mothers, children and the elderly, were waiting outside when the Herald was filming, but McIndoe said the line is normally much bigger.

“Usually, the line goes to the road. [It’s] just crazy,” he said.

Sonya Inifi took her place in the queue at 6.15am on behalf of her dad, who had the flu.

She said the wait times were “ridiculous” but even worse if you arrived late in the morning.

“If we come after say nine or 10am, then you’re looking at like a five-hour wait and my dad’s sick.”

She said it was obvious doctors and nurses at the clinic were under a lot of pressure.

“I see how stressed they are. Their staff (the clinic’s GPs and nurses) aren’t appreciated, and they haven’t been valued (by the Government) for the work that they do. The doctors are for our kids, for our people, for our families.”

She wanted more action from the Government.

“It’s one of the major things that need to be reconsidered, especially the wait times.”

Primary care is ‘on its knees’

McCann told the Herald the queue outside the Ōtara clinic was a symptom of the “significant challenge” general practice is facing.

“It’s absolutely heartbreaking. We don’t want our patients, our communities, experiencing this. People are desperate to access healthcare,” he said.

The Ōtara clinic is categorised as a “very low-cost practice” – one that gets additional funding to reduce fees so its clients, mostly Māori and Pasifika, can access care.

But myriad issues, including staff shortages, burnout, and an ageing population with more complex and chronic health needs, were causing serious issues.

Ambulance “ramping” – where patients are delayed getting to a hospital bed – is seen as partly due to poor access to primary care, which plays a key role in early detection of problems and preventing serious illness.

GPs are also managing patients who need surgical intervention longer.

McCann said the way GPs were subsidised by the Government was outdated – a concern backed up by several government reports, including the Sapere Report, commissioned by the last Labour Government.

“Primary care is absolutely on its knees. We’re seeing a number of clinics close throughout the country. We’re seeing a number of general practitioners just call it quits because it has got really hard,” he said.

“People are doing work in their own time after hours.”

McCann said general practice wasn’t given the recognition it deserved when considering the overall health of New Zealanders and the functionality of the health system as a whole.

He said when general practice operates well it reduces pressure on hospitals, but said GPs had faced “years” of underinvestment.

“If we have more upfront investment in primary and community care and earlier detection, we stand a better chance of actually keeping people healthy; keeping people in their homes as opposed to in hospitals.”

Last month, the Government offered a 4% increase on the amount a general practice gets paid per patient, which McCann said was “not enough”, arguing a “substantive increase” was required.

He said Health Minister Dr Shane Reti had long “signalled” he wanted to invest more in primary care but those on the frontline were yet to see any significant action.

McCann felt the seriousness of the situation “went beyond the minister” and urged New Zealanders to demand more investment in primary care.

He said it was “great” the Government had put millions into funding cancer drugs but emphasised that it would not make a difference if the “front door” of the health system was broken.

“All of the investment in the best cancer drugs in the world [isn’t] actually going to make a difference to patients’ outcomes [if the cancer isn’t picked up early by GPs].”

The National Party’s big health card before the last election was that it would build a new medical school in Waikato to boost GP numbers.

“I think we’re at the stage where no matter how many new medical student places there are at medical school, no matter how many nurses we train, we’re always going to be playing catch-up,” McCann told the Herald.

Doctor: ‘It’s very stressful when you see the queue’

When the Herald visited the Ōtara clinic, one of its 12 doctors, Dr Niroshika Kotte Arachchige, had been called in to help on her day off because staff were overwhelmed.

She and her colleagues see up to 350 patients a day and despite having a dozen doctors it was “still not enough”.

“For example, today is my day off. But my roster manager called me and asked if I can help the queue because there’s not enough doctors. Two of our doctors are down with Covid,” Niroshika told the Herald.

The week before, she was also called in on a day off and ended up working a 13-hour shift.

She said her nursing colleagues were also “exhausted” and believed fixing primary care should be a priority if the Government was serious about trying to reduce the burden on hospitals.

She also regularly did extra work outside of her normal hours.

“I normally come one hour early to do my inbox and my paperwork. On top of that paperwork, we get a lot of [patients] discharged from the hospital to follow up.”

Her greatest concern was her patients, some of whom had to be turned away even if they queued up early.

“So sometimes those who wait for four or five hours have to go home at the end of the day without seeing a doctor.”

Minister: ‘Queues at any practice are concerning’

Health Minister Dr Shane Reti told the Herald early-morning queues outside the Ōtara clinic were not acceptable.

“I understand this particular practice may have faced challenges for some time, but of course that doesn’t make current queuing any more acceptable,” Reti said.

He acknowledged “long-standing” pressure on primary care and said solutions for GPs and patients relied on recruiting and retaining more doctors and improving remuneration.

Reti said the proposed new medical school would help keep more medical students in New Zealand, and in the meantime suggested greater use of healthcare assistants and technology to ease the patient and paperwork burden for GPs.

The 4% pay increase for GPs included a provision which allowed practices to increase their fees to achieve a total boost in revenue of 5.88%, he said.

The General Practice New Zealand chairman, Dr Bryan Betty, said the offer “does absolutely nothing to address the history of chronic underfunding”.

Reti, who practised family medicine for 16 years in Whangārei, “sincerely valued” the contribution of his former colleagues but said no Budget could deliver everything all groups hoped for.

Michael Morrah is a senior investigative reporter/team leader at the Herald. He won the best coverage of a major news event at the 2024 Voyager NZ Media Awards and has twice been named reporter of the year. He has been a broadcast journalist for 20 years and joined the Herald’s video team in July 2024.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you