Director: Colin Trevorrow

Starring: Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Vincent D’Onofrio

3/5

In the best monster films, the creature-at-large should always be a metaphor for something else. In Godzilla, the beast personifies the atomic terror of 1945. In Alien and its sequels, the xenomorph compounded fears of not being alone and superior in the universe. King Kong became a parable on slavery in America.

By wrapping these searching and troubling symbols into a popcorn-crunching piece of entertainment theatre, even the most frivolous filmgoer could be forced to confront aspects of life otherwise unseen. The original Jurassic Park possessed some of this nuance. Jeff Goldblum’s incorrigible character points out that “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, that they didn't stop to think if they should.”

Jurassic World, a reboot of Steven Spielberg’s 1993 hit and its floppy sequels, nods suggestively at Goldblum’s moral dilemma, but is never involved with what anything means.

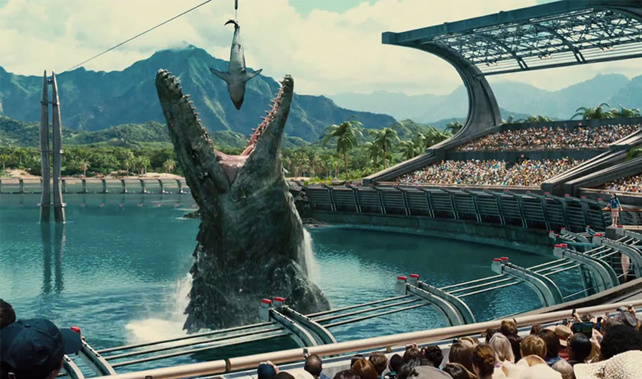

The rampages return to Isla Nubar, scene of Dr Howard’s last fateful attempt at creating a theme park of free-roaming dinosaurs. His vision now fully realised, some 20,000 people are on the South American island to be thrilled by the prehistoric potpourri. Among them are young brothers Gray and Zach (Ty Simpkins and Nick Robinson, echoing Ariana Richards and Joseph Mazzello twenty years earlier). Their aunt Claire (a neurotic Bryce Dallas Howard) runs the park with corporate considerations well to the fore. Chris Pratt, relishing his recent turn as an action star, plays Owen Grady who ‘trains’ Velociraptors as if they were nothing more than zoo lions.

When profit demands, the park’s scientists create a hybrid monstrosity – a spliced and coded killing machine which breaks loose and begins chomping unsuspecting tourists.

Of course, a film about dinosaurs on the loose is never about fulfilling character arcs or punishing emotional trauma. Director Colin Trevorrow seems to have understood this quite well as there is almost no attempt made to imagine his human subjects as anything more than scents to be tracked and prey to be hunted. This might be justifiable if so many hammy performances weren’t phoned in by the likes of Vincent D’Onofrio and Irrfan Kahn – their presence more distracting than forgettable.

If Homo sapiens aren’t up to the job, it falls to digitally-rendered monstrosities to provide entertainment. Between the clawed feet, screeching roars, and the thump-thump-thumping of distant dinos, there is some real excitement. Seeing faceless tourists plucked into the sky by Pterodactyls is immensely enjoyable.

The landmark visual effects of 1993 are thrown entirely in favour of almost-entirely CGI creations. When latex-clad analogues are introduced for close-shot scenes, pointless 3D robs them of tentative believability.

As mentioned above, Trevorrow and the four-strong writing team aren’t concerned with the tensions and depth that made Spielberg’s original so noteworthy. The director, in a pre-release interview stated “I don’t think it’s a message movie and I’m certainly not here to preach” before going on to note the King Dino in Jurassic World represented “our greed and our desire for profit.”

Trevorrow, it seems, is entirely without a sense of irony. This film is laced through and through with product placements for cellphone companies and car manufacturers – even invading the dialogue itself. Could there be a more obvious self-denying metaphor?

For the reasons listed, Jurassic World won’t take its place alongside Godzilla, Jaws, King Kong, or Alien. The villainous creation of mad corporate science isn’t threatening enough, nor does it have the potential for iconic status.

Take your Radio, Podcasts and Music with you